The yachting world recently mourned the loss of one of yachting’s most respected journalists, Bob Fisher. His involvement in, and love for the America’s Cup was well known. Although he understood the importance of development in the sport, he often reflected on a very different time when boats were boats, and challengers were many. Here Bob reflects on the ‘good, old days’.

How the America’s Cup began for me

It began for me in 1945 in the Fisherman’s Shelter at the top of the Hard at Brightlingsea in Essex, one of the East Coast ports that supplied the crews of the big yachts in the days between the Wars. They fished in the winter and went ‘yachtin’ in the summer. For them the summers were months spent away from home and the racing was a highlight.

Those who had been involved with the Cup, were plainly evident, wearing the Guernsey sweaters with those yachts’ names emblazoned across their chests – Shamrock RUYC1 or Endeavour RYS.2. They had been there and were proud of it, the men who told the stories that captivated the imagination of this 10-year-old schoolboy who had already learned to sail. They told of the hardships with a smile. Compared with many of their compatriots, they were relatively well paid, but their seasons were well marked. Their potential to go fishing, for instance, was on a fixed day when they had to be available to be chosen by the fishing skippers – and that was to play a major part one year.

Most of all, the fascination was with the tales of the races. How they won and how they were beaten. They were stories always biased in their favour or how they were ‘cheated out of victory’. But for all that, they were the only contact that I had with the Cup at that time. When I began my serious research, I would learn a slightly different story.

John Bertrand and Alan Bond at the press conference

Reviving the Cup

To find out more about the Cup proved difficult 70 years ago. No one, in the stringently controlled era immediately post-war was thinking about challenging for the Cup; even the thought of preparing huge sailing yachts, let alone building new ones, was far beyond the compass of anyone.

This state of affairs began to change when, in 1948, the commodore of the New York Yacht Club (NYYC), DeCoursey Fales, met Captain John Illingworth, commodore of the Royal Ocean Racing Club and the man who instigated the Sydney-Hobart Race, to discuss the possibilities of racing using the new International Cruiser Racer rating rule with yachts from the 48ft waterline. These discussions came to nothing.

Dennis Connor

Eight years later the new commodore of the NYYC, Henry Sears, on a visit to Britain, met with Sir Ralph Gore, the commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron (RYS), to investigate ways of reviving the Cup races. The result was revealed on the eve of the NYYC Annual Cruise when Sears told the meeting of yacht owners that the New York Supreme Court would be approached to revise the Deed of Gift to allow smaller yachts to compete and the proposal was for 44 to be the new minimum rather than the 65 feet demanded by the Deed.

Bringing in a new class

His new proposed limit was designed to allow yachts of the International 12-Metre class, about half the size of the J Class, which had competed on the last three occasions the Cup had been held. It wasn’t totally popular with all the members of the NYYC – some saw the silver ewer as an icon of the club, a jewel held in an octagonal room of the West 44 Street clubhouse. The club had held it for 106 years and some members thought it was a mistake to start again.

Australia II and Liberty

Many others adopted a more practical approach and were determined to defend any challenge. One very shortly came from the RYS, determined to lead the way. At university at the time, my information came from the Daily Telegraph and the Sunday Times as well as the yachting magazines that I read in an attempt to be well informed of the movements of the British syndicate’s choice of designer and builder of the yacht, Sceptre, as well as the trials in the US for a suitable defender from the handful of 12-Metres in Newport, Rhode Island (RI).

Columbia, skippered by Briggs Cunningham, met Sceptre, steered by Lieutenant Commander Graham Mann in the 1958 challenge – the first for 21 years. However painful it was from my point of

Columbia, skippered by Briggs Cunningham, met Sceptre, steered by Lieutenant Commander Graham Mann in the 1958 challenge – the first for 21 years. However painful it was from my point of

view, the general delight was that the America’s Cup had been saved. Sceptre was badly mauled by Columbia; the 4-0 scoreline hid the massive time differences.

The Australian charge

The hiding that the British had received destroyed all interest in the America’s Cup at home and it was difficult to keep up with the 1962 challenge from Australia’s Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron (RSYS). Time was ripe for a change, according to Sir Frank Packer, who was leading the Aussie charge. A newspaper owner, he had the necessary muscle financially as well as the means of publicity.

Packer made the masterly stroke of chartering the pre-war 12-Metre Vim that had run Columbia close in the trials and then chose Alan Payne to design his new boat, Gretel, named after his wife. While in the US, Bus Mosbacher with Weatherly won the selection trials to face Jock Sturrock with Gretel in the 1962 event. It was close, with Gretel winning the second race, but the Cup was retained by the NYYC by 4-1.

The success of the 12-Metres

Immediately thereafter a challenge was received from the Royal Thames Yacht Club (RTYC) for a series in 1963, but was rejected by return by the American club as not giving sufficient time for the preparation of a suitable defence. The RTYC was, however, persistent and immediately re-challenged for 1964 and this time was successful. 12-Metres were regularly racing in Britain and they were joined by Tony Boyden’s Sovereign in July ’63, at first on the Clyde where she raced with Sceptre.

John Bertrand and Alan Bond

at the presentation of the cup

Meanwhile in the US, four 12-Metres competed for the right to defend the Cup. Weatherly was back with Columbia and Nefertiti, and they were joined by Constellation, an Olin Stephens creation.

Very soon it became clear that Stephens had produced a super-boat and it took very little time to decide that she should defend against Sovereign.

Sovereign was no match for Constellation – it was all over in four races, all won by substantial margins by the defender (one by more than 20 minutes). There was no hope too for a British challenge next; a sealed bid from the RSYS claimed match for Australia in 1967.

Australia II

Other challengers enter the frey

Then there was the added attraction of a further challenge from the Yacht Club d’Hyeres, which was accepted. Baron Marcel Bich, founder of the Bic Group, would have to wait. (His 1970 challenge was to be the first from outside the English-speaking world). Meanwhile, there were two Australian challengers and the elimination of one had to be dealt with at home. This was between the Melbourne syndicate led by Emil Christensen with the Warwick Hood-designed Dame Pattie and the much-modified Gretel of Packer’s syndicate. Packer lacked a good crew for Gretel as most had followed Sturrock on to Dame Pattie. These trials were very one-sided and the Melbourne boat’s crew could be heard singing that South Pacific favourite: ‘There is nothing like a Dame.’

In the US, Stephens produced another stunning 12-Metre, Intrepid. She successfully defeated the other three 12s entered in the defence trials, Constellation, American Eagle and Columbia, and was chosen to defend the Cup. It seemed she would have no difficulty in dealing with Dame Pattie in the 1967 match and so it was no surprise that she won 4-0 with average margins of four minutes. Once more the Cup remained with the NYYC.

The America’s Cup in the ’70’s

In 1970 multiple challenges began. Not only did the defenders hold their elimination trials on the waters at Newport, RI, but so did the foreign challengers. In this case it was Bich’s France and Packer’s Gretel II. Bich’s first challenge was a brave affair but faltered in the face of Packer’s experience. Bich’s management style of sacking helmsmen who failed against Jim Hardy sailing Gretel II was disastrous and finally ended in Bich himself steering the French challenger in defeat.

In the meantime, the defence candidates, Valiant, Intrepid, Weatherly and Heritage, held their elimination series. The first of these was the NYYC Annual Cruise and the results pointed to Intrepid and Weatherly being the best of the bunch. Work was done on all the boats and there was all-round general improvement for the final trials with Intrepid, steered by Bill Ficker and with Steve van Dyke as tactician, beating Valiant and chosen to defend.

In the meantime, the defence candidates, Valiant, Intrepid, Weatherly and Heritage, held their elimination series. The first of these was the NYYC Annual Cruise and the results pointed to Intrepid and Weatherly being the best of the bunch. Work was done on all the boats and there was all-round general improvement for the final trials with Intrepid, steered by Bill Ficker and with Steve van Dyke as tactician, beating Valiant and chosen to defend.

The match was notable for several reasons, the first of which was the prolonged protest by Gretel II at the start of the second race. She had luffed Intrepid at the start and the jury found in the defender’s favour but the Australians persisted with the protest albeit without success. It did, however, provide me with an opportunity to view my first America’s Cup race. I had caught an early flight to New York, rented a hire car and made my way to Newport, RI.

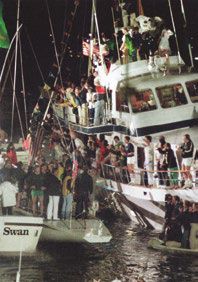

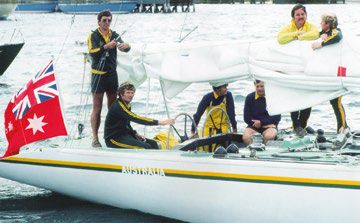

Around Australia II after victory

Covering my first America’s Cup race

Once in RI I traced media contacts and managed to claim a berth on the press boat for the day – it was to be the fifth race with the score at 3-1 to the defender. Hardy won the start with Gretel II by a second, but there his superiority ended. Ficker soon took over the lead with Intrepid and settled the issue for the defence. I was disappointed but joined the general celebrations, meeting old friends and finding a bed for the night. I returned to New York early the next day and caught an overnight flight back to London determined to see more of the next America’s Cup racing.

A change of employment guaranteed that determination; I was in Newport, RI some four weeks before the 1974 Cup and was able to see the trials of both the defenders and the challengers. And that was a true festival of yacht racing. The home team (the best way to describe the group of 12-Metres from a varied group of clubs) was bound to be powerful. It included the two-time winner Intrepid, rebuilt to Britton Chance designs for a West Coast syndicate and sailed by Gerry Driscoll, a former Star world champion.

Causing a stir

Mariner, also a Chance design, caused the most comment, even more than the skipper, Ted Turner, in his first Cup foray. Mariner had a strange underbody format, bulbous with a squared-off back end, which led Turner to voice, what we all thought, to Chance: ‘Hell Britty, even turds are tapered!’ But Chance had relied (too much it turned out) on the results of tank testing.

Ted Turner on Courageous

Valiant, Mariner’s stablemate, was launched soon after, and some days after the new Sparkman & Stephens design Courageous, the first American aluminium boat to be launched. Mariner had the first meeting with Intrepid and provided a moment of truth when the latter pulled out from under the new boat’s lee.C

It was obvious to everyone that Mariner was slow, dreadfully slow. When the final defender trials began, Driscoll skippered Intrepid against Bob Bavier in Courageous, and Dennis Conner in Mariner against Turner in Valiant. Wins went to Intrepid and Mariner. The next day it was Mariner versus Intrepid and Courageous against Valiant. The winners were Intrepid and Courageous; that same result was true for the second race of the day.

Challenger of Record

The Royal Thames Yacht Club were the challengers on record but withdrew leaving the Royal Perth Yacht Club in for Alan Bond’s Bob Miller (later Ben Lexcen) designed Southern Cross to fight a one-sided match with the Yacht Club d’Hyeres with Bich’s France. Bich had had a heated argument with Paul Elvström and in doing so lost his prestigious helmsman. The 4-0 whitewash handed Bond the challenge on a plate.

Australia II

As it later became clear, Bond’s role should have stopped at financing the challenge and the strategy placed in the hands of someone who knew the game. He had initially appointed John Cuneo, the Dragon gold medallist in the 1972 Olympics, as skipper, but what he needed was the wisdom of Warren Jones as general manager.

Just before the match was due to start, and the decision of who would skipper Southern Cross had not been made, I was having a quiet evening in the Black Pearl (a bar/restaurant on Bannister’s Wharf, a centre of Cup activity) with Jim Hardy and Tom Blackaller. The skipper subject reared its head. It ended in a bet – a case of Hardy’s Show Port from Jim against my stake of a

case of Taylor’s that Jim would be chosen. History records that I won and I didn’t need Blackaller’s witness to claim my Port!

But Southern Cross was not ideal for the lighter winds of Newport, RI. Miller had designed her with a long waterline and that made her short on sail, which was the opposite of the American boats. After a defeat in the first race by Courageous, Bond changed his afterguard replacing Hugh Treharne with John Cuneo as tactician and Ron Packer with Jack Baxter as navigator. It made no difference to the results. The Cup stayed with the NYYC.

The challengers

There was a pause in the challengers for 1977; the first came in late April 1976 and from a new club. The Royal Gothenburg Yacht Club (GKSS) from Sweden provided the challenge for a new skipper, its most successful sailor, Pelle Petterson. An industrial designer, the Volvo P1800 was one example of his work; Pelle designed his boat based on his experience from Courageous, Intrepid and Columbia, which the syndicate had purchased. As might be expected the Swedish 12, Sverige, was very different. She was steered by a tiller and her winch mechanisms were below decks and powered by men with their legs.

That year’s event also marked the reappearance of Bruno Troublé at the helm of the French challenger. Bich arrived in Newport, RI with France, France II and Constellation and appointed Troublé as skipper of the fastest, France, rather than Poppy Delfour or Jean-Marie le Guillot.

Australian challenges for the Cup this cycle were mixed and varied. I was sailing with Ben Lexcen on More Opposition, the ocean racer he had designed for Tony Morgan, as he was living in Cowes and working with Johan Valentijn who had learned his yacht designing with Sparkman & Stephens. Bond made repeated efforts, by telephone, to persuade Lexcen to design a 12 for him, without success. Finally he travelled to Cowes, where he met him in a supermarket and finally sealed a deal. It included Valentijn whose knowledge of Sparkman & Stephens was essential towards the eventual success of Australia. For his skipper, Bond chose Soling champion Noel Robins, an old friend of mine.

There was also a challenge from Sydney. Hardy twice tried to buy Gretel II from Bond but each time the price was too high. Finally the boat changed hands, but to Gordon Ingate, who asked Payne for some alterations in line with the new class regulations. Ingate gathered an experienced crew of 12-Metre sailors who arrived in Newport, RI, in shirts bearing the words: ‘Daughters of America, lock up your mothers.’ Unforgettable!

There were four challenges, two from America and one each from France and Sweden. To face the best of them the NYYC assembled Courageous, skippered by Turner, and Independence with Ted Hood on the East Coast while from California, Lowell North trialled the new Enterprise with Intrepid. Despite restrictions on sail purchasing, Turner was the clear winner of the US trials and selected to defend.

Meanwhile the challenger trials stood at Australia 5-2, Gretel II 4-2, Sverige 4-3 and France 0-6. The semi-finals were a knockout around the full 24,3 mile course, Australia vs France and Gretel II vs Sverige. Bond made a crew change that raised eyebrows by nominating American tactician Andy Rose, my old friend from Congressional Cup days and twice-winning tactician of that prestigious match racing event. He had coached the Australians in 1974 and was known in the Australian press as a Californian rather than an American.

The US trials

Turner and the Courageous crew with Gary Jobson as tactician, did a masterly job of winning the US trials. At one stage the scoreline read: Courageous 10-1, Enterprise 4-7, Independence 1-7. Turner and Courageous were chosen to defend. It was one-way traffic in the Cup with Courageous never headed in the four races. Turner was unstoppable. He purchased Courageous and Intrepid from the Kings Point Fund but didn’t have the time or desire to practise as much as Conner, as he explained to me one morning at breakfast in 1980: ‘140 days last year, 140 days in a sailboat – that’s what he spent – and him a fully grown man’.

Lionheart

Bond was back in 1980 with Australia, and France with Bich’s new boat, and Petterson with a modified Sverige, but also a British challenge from the Royal Southern Yacht Club, with John Oakeley in Lionheart.

My personal attention was with this boat as I was sailing Solings with Oakeley at this time. She had a bendy mast rig, which allowed extra area in the mainsail. It was a design invention of Oakeley’s, which was copied by the Australians, albeit clandestinely and for a long time unknown to Bond. Oakeley had supervised every stage of Lionheart’s design and build and every slight difference of opinion was seized on by the syndicate. Eventually they sacked Oakeley and appointed Lawrie Smith as the new skipper.

I hated seeing Oakeley go for I knew the syndicate had made all the mistakes, principally by denying him the freedom he required to make the necessary changes to the boat and insisting he stayed to the standard line when it needed thinking outside the box.

In the challenger trials France III beat Lionheart and Australia beat Sverige. In the final between Australia and France III}, Australia was 3-0 up before Troublé hit back with a win for Europe. After a lay day Hardy scored the series-winning victory for Australia. But who would they meet in the match? Conner in Freedom, Russell Long with Clipper or Turner back with Courageous? Turner was the first to be ‘excused’ from the trials and four days later Conner was chosen to defend the Cup. He began the defence on 16 September, his 38th birthday, with a win. The next race was abandoned when the time limit was exceeded. Australia won the resail but that was the end of her challenge. Conner in Freedom won the next three races by increasing margins.

How I covered the racing back then

All these races I covered for The Guardian newspaper, filing my reports from the press boat by radio through a local station with collect calls to the copy taker in London, in the same way as Stan Zemaneck was filing his radio reports for 2UE in Sydney.

For the next Cup, in 1983, we prepared in advance by going to New Bedford Radio Station armed with presents of whisky and boxes of chocolates for the operators and a short list of the numbers we would require. It worked perfectly. By 1983 I knew Newport, RI fairly well as I had been going there frequently to sail aboard a variety of boats in search of material for magazine articles and knew many of the Cup sailors. It made life much easier that an English sailing friend opened a bar/restaurant almost directly across Thames Street from the Armory – Zemaneck, his wife Marcella and I used to dine there on most race days.

1983

It was a year with three defence syndicates and challenges from five countries: France, England, Italy, Australia (with three separate clubs) and new boys on the block, Canada. The defence looked strong. David Vietor had purchased Courageous, convinced that she was the fastest all-round 12 and sailed her on the West Coast with Blackaller and Jobson’s Defender, their new Pedrick design that was constantly in the boatyard for minor alterations.

Parallelling them, Conner took delivery of his Sparkman & Stephens/Valentijn designed Liberty, which cunningly was measured for three different certificates and preserved the ability to change to their respective measurements overnight. He was, to all intents and purposes, campaigning three boats. Mid-season new sails made Courageous faster, but not quite fast enough, and after the final trials, Conner and Liberty were chosen to defend the Cup.

The challenger trials

The trials were more interesting because of the unknown shape of the Lexcen- designed Australia II. Bond’s Svengali, Warren Jones, insisted on skirting the underwater sections of the new boat Around Australia II after victory Ted Turner on Courageous from the very start. No one outside the Bond team was allowed to see the keel and underbody that Lexcen had created with the help of the Dutch testing tanks at Wageningen. Frogmen from other syndicates made attempts but were generally seen off by Bond’s similarly attired guards. One of the abilities that the underbody shape provided Australia II was to tack faster than any of her rivals. In early trial matches, it was discovered that Australia II had poor performance downwind and a massive spinnaker development programme was undertaken that eventually produced the winning weapon in the Cup.

Zemaneck and I were ‘helping’ each other on the press boat – I kept a record of the time differences at the marks and we swapped comments on the performance of John Bertrand and his afterguard on Australia II and that of Conner and his assistants on Liberty. ‘Same old story’ we agreed after the first race when Liberty took the lead on the third leg and won by 70 seconds thanks to a steering failure on the second beat.

Further damage, this time to the head of the mainsail on Australia II, allowed Liberty to cross the finish line 1:33 ahead, but there was a protest from the Aussies over a slam-dunk tack in which the lead changed hands. Bertrand wrote of the issue: ‘In a split-second decision, I tacked the boat, narrowly missing them as they tacked on our bow. If I had not moved, we would have crashed into them, of that I am certain. I cannot believe what they have just done.’ Nevertheless he lost the protest and the race. The score was 2-0 in Conner’s favour.

Race 3 was abandoned when the time limit expired with Australia II almost six minutes in front. Conner had been kept informed on the amount of time he had left to beat his rival by his navigator, Halsey Herreshoff. ‘When it got to where they had to go about 1 000 miles an hour, we knew they were in trouble,’ he said, adding, ‘God must be an American.’

Mainsail trimmer John Marshall believed Liberty could be improved by going to her light-air configuration by changing her certificate with a new measurement. It may have done, but not by enough as was revealed when the race was rerun and Australia II streaked away to win by 3:14.

Conner was asked at the press conference whether God, who he had said the day before was an American, had had the Sunday off. He replied: ‘No, but even he couldn’t cope with Australia II today.’

After a lay day Conner and his crew sailed Liberty in a ‘perfect’ race in eight to 10 knots of southwesterly breeze, finishing 43 seconds in front to lead the series 3-1. He needed one more win to retain the Cup. The next race was in the region of 18 knots and Bertrand, trying to force Conner over early, was caught out. He started 37 seconds behind after beating the gun by a second and having to restart. Conner’s boat was wounded – a jumper strut had failed, and Australia II gained on every leg of the course to win by 1:47, making the score 3-2. The following race

was scheduled for the next day.

The deciding race

Australia II was 3:46 up after the first round and Bertrand covered Conner’s every move from then on to win by 3:25 and level the score line. It meant that the outcome of the series and the ownership of the Cup would be decided by the final, seventh race.

Aboard New Englander II, the press boat, Zemaneck and I prepared for the decider, as we called the race, on Saturday 24 September. Liberty had been reballasted to another measurement and certificated.

Above the start, helicopters circled the Goodyear blimp one way and fixed wing aircraft the other – it was more like a scene from Apocalypse Now. With 90 seconds to the start, it was postponed. It was half an hour before course signals were rehoisted and, for the sixth time out of seven, Conner won the start and was 29 seconds up at the windward mark.

He stretched that to 45 seconds at the wing mark, but on the next reach, which had become more square with a shift in the breeze, Australia II closed to 23 seconds. Zemaneck and I looked at each other – I was filing my copy in holding paragraphs and he was breaking into broadcasts on 2UE with updates. When Liberty rounded the weather mark for the second time with a lead of 57 seconds, most people thought the race was over, but Conner made a classic mistake. He failed to cover. Worse than that, he gybed away. For two minutes he allowed Australia II to sail away in the southerly breeze and when he came back, still marginally ahead, he met his match. The spinnaker that Australia II had been working on was only 34 feet across and would run deeper than that of Liberty, which was 37 feet and far less stable. It was 20 minutes before Conner gybed and crossed closely behind Australia II.

There were four more gybes apiece before the leeward mark was rounded with Australia II 21 seconds in front. Could Bertrand hold on to this lead? Zemaneck was locked on to 2UE and I was keeping him abreast of the scene. It was tack and counter tack, 47 of them before Australia II crossed the finish line 41 seconds before Liberty.

The America’s Cup had changed hands and Zemaneck was giving his listeners his all. Then he handed the microphone to me for comment before closing.

A good ending

We returned ashore, after I had filed my copy right on the final deadline. The press conference was a wild one and I still had a magazine story to file by telex. That was do-it-yourself, and I was new to this technology – it took ages to cut the tape – so that when I emerged from the Armory, Thames Street was a sea of detritus. I made my way to where I knew I would find a drink – the Aussie press house. And I was right.

Next morning I caught up with Warren Jones as he made his way to the boatyard where he had left his bicycle. He looked as if he had all the cares of the world on his shoulders. ‘Hangover?’ I enquired. ‘No, Fish, I only had two beers.’ ‘So, what’s troubling you?’ I asked. ‘I just can’t think where in Fremantle we are going to hold the America’s Cup Ball!’ he replied.

It was the end of an era.

RIP Bob!

This article was adapted form an article that first appeared in Sail + Leisure magazine.