Alicudi and Filicudi are the least explored of Italy’s Aeolian islands, where days roll on without flash or fuss. If you’re looking for a place to start your travels this summer, perhaps this could be the best way to ease into a summer in the Med.

The unknown archipelago

Take an archipelago of seven small islands smelling of wild fennel and the open sea. Volcanic, sky-thrusting. Scattered 50 miles north of Sicily, the Aeolians are thought of throughout Italy as beautiful and natural – but mysterious. Volatile. Some 60 years ago they were near-deserted but have since been passing between them the baton for southern Europe’s most rugged glamour. Sometimes it’s Stromboli (beloved especially of Neapolitan left-wingers) and sometimes Panarea, and yet… two islands at the far western tip, Filicudi and Alicudi, remain a puzzle, suspended at a distance.

On the more populated Salina, I sit in the village of Pollara in an orange fuzz of apricot trees, waiting to sail. Hedges vibrate with bees. It’s quiet – just a few people at a café, reading La Repubblica. And quieter still inside the chapel St Onofrio in the main square, where a statue of the saint – a fourth-century desert vagabond – stands completely swathed in beard and spring leaves, under a gold-starred dome. During the afternoon, in a hotel restaurant somewhere, prawns from the bay cook in sticky Malvasia wine, sweetly stinking out the coastal path. I sit with a couple of elderly islanders on some steps as they look across the sea, oozing fatalism. Last night, they say, there was a green ray right across the horizon: rare and wondrous. We cast our eyes for what feels like the thousandth time at Filicudi, 27 miles away. It’s a smudge on the horizon, wearing a dollop of scudding cloud over its extinct volcano like an insouciant lace hat.

Filicudi

Captain Pierre takes me there; two hours gliding on his wooden craft, the Barca Jost, describing Filicudi as a place of eccentric pilgrimage. ‘There might be intellectuals on those islands,’ someone had said to me a couple of days before, perhaps still envisaging the ‘radical chic’ who went that way in the late 1970s – Memphis designer Ettore Sottsass, the novelist Roland Zoss – finding a quiet welcome among its few residents; fishing and cultivating capers and grapes. A tuna the size of a junior piano flings itself up as the black boulders of the island loom. They’re studded with a few naked sunbathers, nudged from their sun daze by the chug of our engine, heads draped in sexily shredded straw hats. One girl – a siren, a narcissus – has hair like seaweed streaming down the shimmering basalt

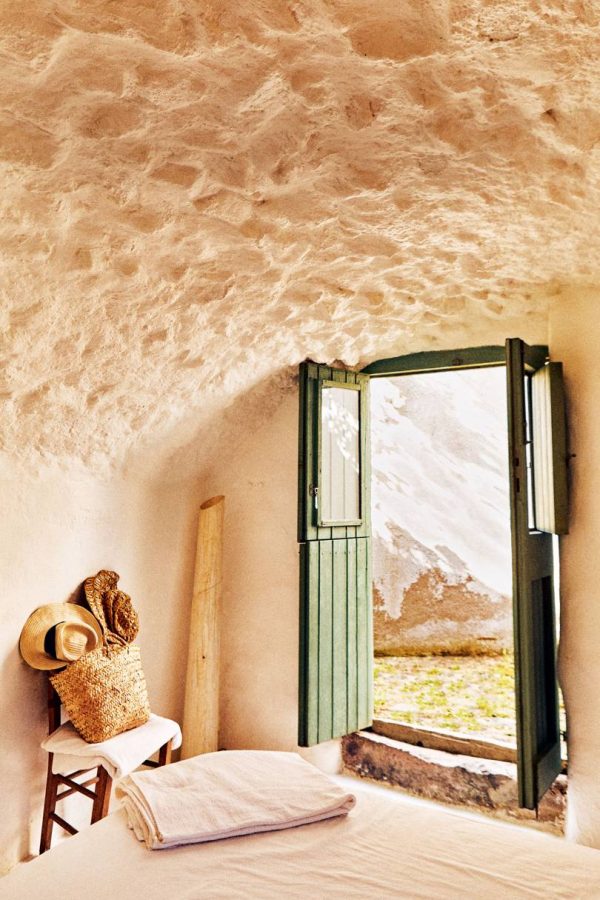

I take a wooden seat in the bar of Pensione La Sirena along the seafront in Pecorini a Mare, the prettier of its two ports. Children politely play Monopoly in the shade. There is to the hotel – and the whole island – something of Fifties Algiers. Tiles and fans and dust. A young man, pale, like he’s on the run from something, sits in the corner with a rucksack, reading (yes!) Camus. Shaped like a miniature amphitheatre, Pecorini’s one road is littered with squashed lemons that give a drifting aroma of pine and sherbet. No public transport, just a population of less than 300 living on a caper-bursting landmass smaller than four square miles in high-hill houses with slivers of Aeolian history in their design. A whiff of all invaders and settlers: Greece, Rome, Byzantium. An ancient fear of pirates, especially, in the glassless porthole windows (small, to attract less attention) that seem like vigilant, doomy eyes. Yachts dot the bay. Lolling handsomely is fisherman Antonello Bonica and several of his 10 brothers, the whole lot variations of the actor Mario Sponzo, who plays, with sentimental sighs, the lighthouse keeper in Rossellini’s Stromboli.

Now and again a boat arrives from Naples and someone gets off, dragging a suitcase. During the afternoon, a crowd of people from Turin motor in from offshore for a great mound of spaghetti alle vongole and then stay into the evening, weaving about the restaurant in thigh-slit dresses and holding babies wearing silver bracelets. The little cocktail bar spreads rugs and cushions along the port, and a party starts – until there’s a power cut, and everybody takes their charisma back onboard or up into the hills, and Pecorini returns once more to just the sound of the sea singing its stony song

Alicudi

Midday at Alicudi’s one port a few days later. An hour away by ferry, some 17 miles from Filicudi, the island rises, smaller, wilder. A population of just 100 in winter. Boats stop for mere moments to perhaps let off a couple of hikers and the once-weekly mail. No bank, no wheels. I toil on foot along stone steps leading steeply from the port. A mule can be hired to follow with luggage and supplies – not a put-upon mule, anguished and drooling on a bit, but one that spends most of its day in the shade by the tide. It was only in the 1990s that the telephone and electricity arrived on Alicudi and for a while all the girls watched soap operas from Venezuela, weeping up and down the street when a character called Salvatore died. A few decades before, the rye fungus ergot was innocently and routinely baked into hallucinogenic bread and people saw flying sorceresses and fancied they controlled the weather with their minds. Some say they still can.This afternoon, old men wilt in a cleft in the rocks, and a schoolgirl hauls a plastic bag heavy with one fat octopus. The brave come to this place to hike. Frugal locals keep gardens of wild spinach and fava beans, and catch rabbits. Everybody is lean and hale, although when a chiropractor visited once, there were queues to see him. I spoon almond granita in the Golden Noir café near the dock, where the waitress smokes testily, as though harbouring secrets, and later visit the island sage, 70-year-old Silvio. In his garden his rough foot lolls on a chair by a decanter of homemade red wine, and he repeats a prayer he casts every Christmas across the temperamental sea, shifting into the arcudaro dialect, hard-edged and melodious, before trailing off to work through a plate of stewed gallinella fish spine and chillies.

There’s a warm silence and an electric-blue vastness of sea below us, holding that purely romantic thing: a single white flash of sails. An atmosphere of people reading or sleeping in villas up steep brooding gorges. The whole place seems to roost like a bird. A couple of walkers suddenly appear, tanned the colour of dry sherry, and quickly run cold water from a public tap over their boots as though putting out a fire. In the grocery store, later, I notice an inordinate amount of biscuits for sale in ornate and gilded packaging. Dry, sustaining food to crunch on, for mustering the strength to walk home – and when I finally do, dust turns to soot as Otto the mule clomps ahead of me with a young peach tree strapped to his saddle. One time, incapable of climbing back down after climbing all the way up, I beg Otto to bring me tins of tuna and a bottle of wine, and when he eventually arrives at my window he wears a wry look, while Bartolo the mule man softly scratches his ears. I rummage for some euros as Bartolo adjusts his straw hat – a creation so patched up, so re-thatched and shaggy, it shakes when he moves, like an immense yellow dahlia.

That night the water in the port is a clean swell of black glass. A few islanders chat to the fisherman Giuseppe, preparing to catch swordfish on an early sail toward Ischia. He stands sentinel, never for a moment off balance on the lurching vessel, with two puppies wrapped in blankets, yet nameless. This is to be their maiden voyage. Quest is their fate, not comfort. It seemed to me infinitely Aeolian: senses never to be dulled by too much ease. Hours later, through my boarding-house window, I vaguely hear his boat start its engine and cast off. In those semi-conscious moments before dawn, any room or world is all aloneness; but in this place, profoundly so. Nothing here but an unlikely dawn sky, streaked salmon like the inside of an abalone shell. Nothing but the sun newly eased from its moorings, starting its sure and baking drift into the great Sicilian emptiness.

Pictures by Oliver Pilcher

Article – CN traveller

Read more:

Amazing food and drinks to have while visiting Italy